Estimated reading time: 26 minutes

Papercrete is Concrete Made with Paper. It’s Inexpensive, Sturdy, Lightweight, Insulating, and Better than Bricks.

Papercrete was invented in the 1920s, but it was so easy to make, no one bought it. Papercrete has been used to build homes, walls, fences, and is easily formed into any object from flowerpots to furniture.

The biggest advantage of papercrete is that it’s lightweight but sturdy enough to bear loads. It also has excellent insulating properties with an R-value of R2 per inch. Better yet, you can use regular hand tools and power tools to saw it, drill it, and you can even pound nails into it.

Want to save this post for later? Click Here to Pin It on Pinterest!

Basic Papercrete Ingredients

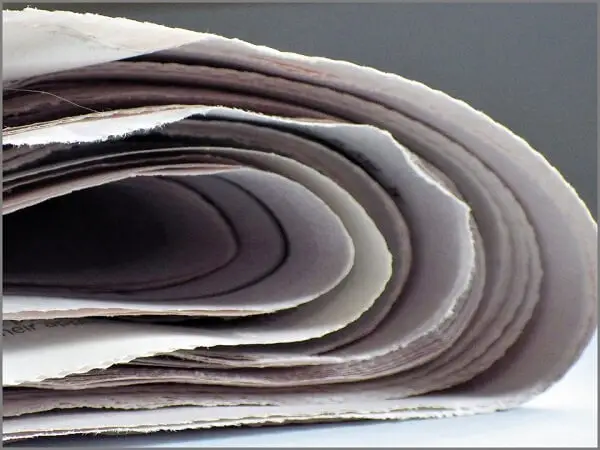

As you would suspect, papercrete starts with paper. Newspaper is the source of choice, but any paper will do including magazines, napkins, paper bags, junk mail, and even cardboard.

They can all be combined in any proportion and are torn into two-inch long strips; soaked in water and then pulverized to a pulp using a plaster or paint mixer or stucco mixer attached to a large drill.

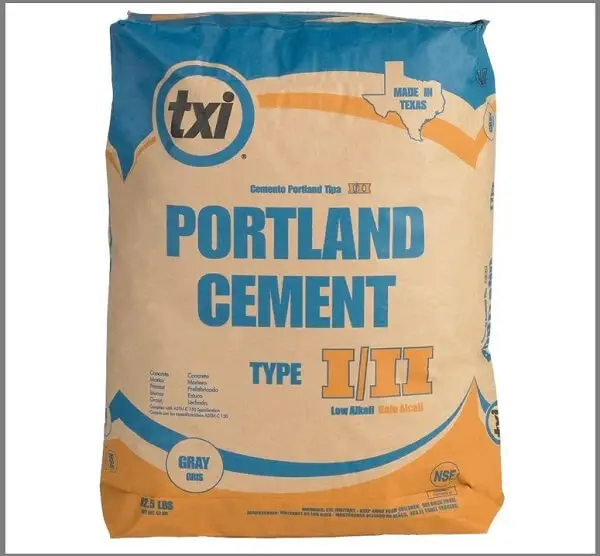

The second ingredient is cement used as a binder. Portland cement is the standard recommendation in a smaller proportion than the paper pulp. The amount of cement can vary but should never be less than 10%.

A filler like vermiculite, perlite, sand, and/or dirt are also added but the proportions and the particular filler varies. Fillers can either lighten the papercrete in the case of perlite and vermiculite or make it heavier and stronger when sand or dirt are used. The choice of filler has to do with the end use.

Load-bearing walls need stronger, heavier materials like sand or dirt while other uses that don't involve a lot of weight or stress (such as a planter) can be made with lighter fillers like vermiculite or perlite.

If you are planning on doing a lot of shaping or cutting of papercrete, you’ll be better off using lighter fillers. You could also skip any filler and go for the strongest mix of just paper pulp and cement.

Serious Off-Grid Papercrete

Papercrete ingredients are essentially on-grid components. If we find ourselves off the grid for any length of time, manufacturing processes to make cement and even paper will be compromised. That’s why we’re also going to cover a pure, off-grid recipe using an ancient Roman formula for cement as a binder and natural cellulose from certain plants.

Clay is another option as a binder, but the unique properties that make papercrete work come from the cellulose fibers in paper. If you can find cellulose fibers in nature, you can improvise without paper.

Papercrete Colors

Straight papercrete is a light grey. It can be painted or stained and sealed with polyurethane. It can also be dyed with commercially available concrete dyes.

Adding a dye saves you from the labor of painting and repainting. You’ll also find the rough texture of papercrete can be difficult to paint, although a paint-sprayer setup could make things easier.

When we explore the off-grid approach to papercrete, we’ll also cover various dyes from nature like the pure blackberry juice pictured above.

What’s the Downside of Papercrete?

A lot of that depends on the recipe and your proportions. A mixture that is high in paper pulp will be lighter, less expensive, have better insulation properties, and will be easier to saw, drill and shave.

Unfortunately, papercrete in general will form mildew if in constant contact with water, especially a papercrete mix made with a high proportion of pulp. It’s easy to seal papercrete to protect it from rain with a water-resistant deck treatment or waterproof polyurethane, but constant exposure to moisture or immersion in water will eventually create a problem.

On the other hand, papercrete with a high proportion of concrete is not only stronger but more resistant to moisture. The tradeoff is that it’s heavier, and added cement means added cost.

Also, papercrete does not bond well with stone or concrete. If you are planning to apply papercrete to one of these surfaces, you’ll have to figure out a way to attach bonding straps, rebar, or some other way to give papercrete a chance to grip the concrete or stone surface.

Papercrete with a high proportion of paper pulp can be slightly flammable. Most reports indicate that it tends to smolder rather than burst into flames, but unlike conventional brick, it should be kept away from flame sources like wood-burning stoves if it has a high proportion of paper pulp in the mix.

High pulp mixes also lack some of the structural integrity of mixtures made with proportionately more cement. We’ll isolate specific blends and proportions based on use, load, and potential exposure to water. As a general rule, you should keep all papercrete off the ground and especially avoid putting it underground or it will eventually disintegrate.

Getting Ready to Make Papercrete

Like any process, you’re going to need some tools, materials, and a cellulose source staring with paper. The amount of paper you need depends on what you’re trying to do. If you’re trying to build a small house, you’ll need a lot of paper. If you’re going to pour your papercrete into a form to create a post or a few bricks, you’ll need less.

If you get a daily newspaper, get it out of the recycling bin and into a paper storage bin. Collect other paper from the mailbox, those old magazines you’ve saved too long, and you can always ask family and friends to pitch in and even store some for you.

If there are plastic windows in an envelope from the mailbox, tear them out. Plastic and papercrete don’t mix. And by the way, who needs a shredder for bank statements and credit card junk-mail when you’re making papercrete.

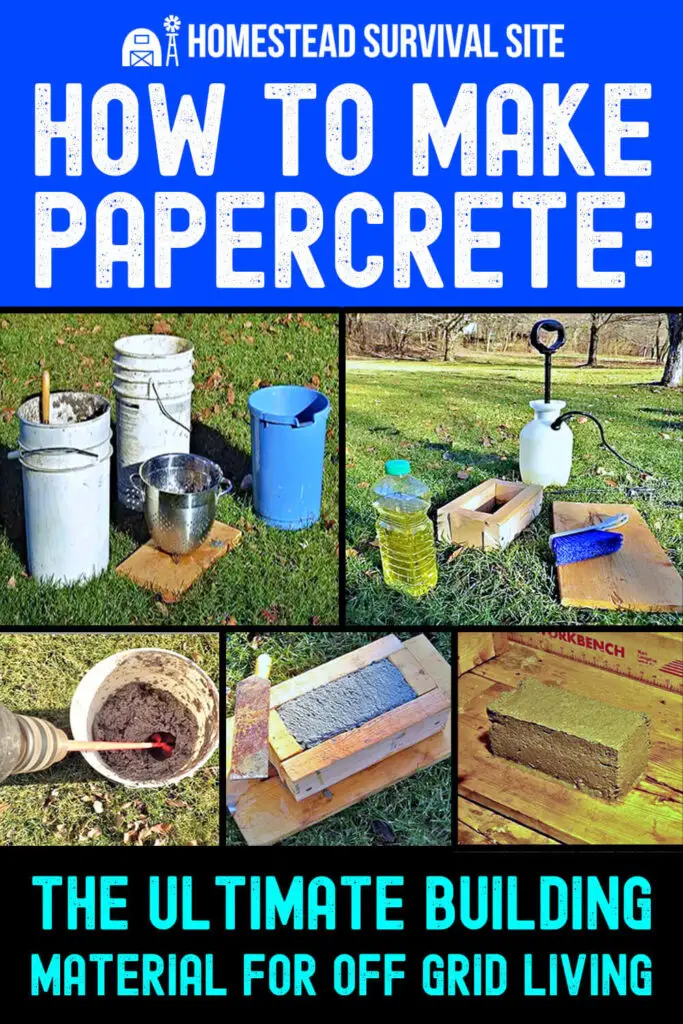

With all of that being said, here’s a short-list of things you’ll need to make a small batch of papercrete that will make 2 to 3 bricks:

- 5-gallon buckets and a colander for draining the paper pulp.

- Plaster or paint mixer attachment or a stucco mixing blade attachment, although the sharp blades of a stucco mixer could cut the plastic sides of a 5-gallon bucket.

- A heavy-duty drill that will accommodate a half-inch bit.

- Enough water to cover the torn paper by two inches.

- Portland cement.

- Vermiculite, perlite, sand, or dirt. (Vermiculite and perlite are light fillers while sand and dirt are heavier and sturdier fillers.)

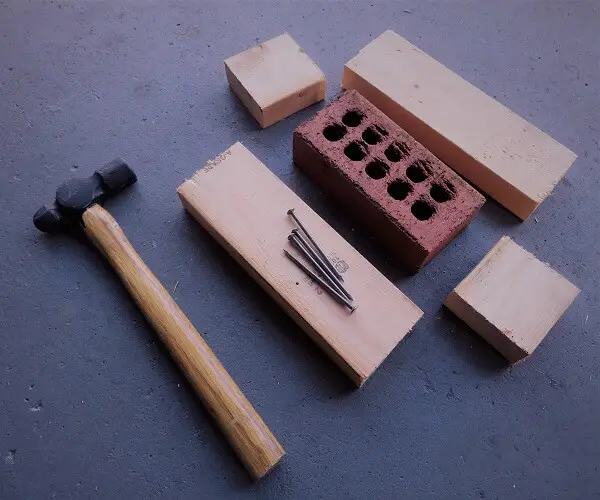

- Wood, nails, and hammer to build forms. If forming bricks, an actual brick will help to determine the size of the form.

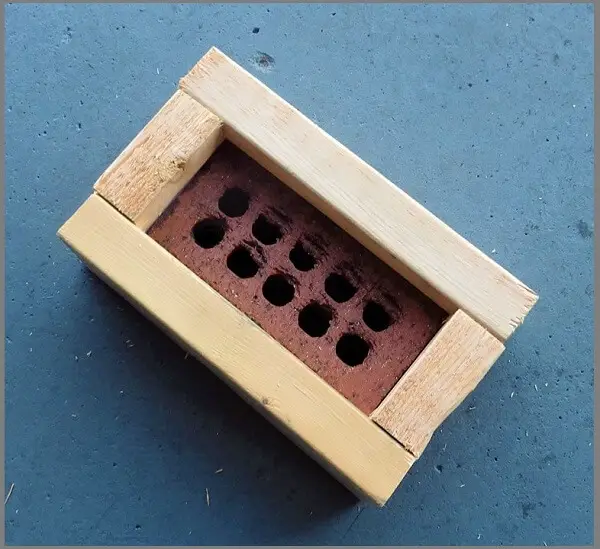

Papercrete Brick Forms

Papercrete is typically poured into a mold or form. Molds are used to shape objects like pots and forms are typically used to make papercrete bricks.

If you are planning on making bricks, you can easily make the brick form out of a 2×4. The standard size for a common brick is 8 x 4 x 2.25 inches. Unfortunately, a standard 2 x 4 is actually 1.75 x 3.75. Neither measurement comes close to 2.25 inches, so you either have to rip the length of the 2 x 4 to get to 2.25 inches or make a larger brick.

That’s okay if all of the bricks you make are the same size, and that’s what we’re going to do here.

Papercrete Release Agents

Any form or mold needs to be coated with a release agent to allow the papercrete to release from the mold or form.

Common vegetable oil works fine, or you can buy professional release agents for concrete at a home center or hardware store. Paint the release agent on the interior of the form or mold with a paintbrush or spray it on for larger projects.

You’ll also need a board underneath the form, and that should be coated with a release agent as well. If you are doing large scale construction with papercrete, you’ll definitely want to use a hand sprayer with a pump to make application to forms faster and easier.

In a serious off-grid environment, you can use animal fat, old motor oil, and even waxes to prevent the papercrete from bonding to the sides of the mold or form.

Paper Pulp Directions:

1. Tear the paper into long, 2-inch strips and drop into the 5-gallon bucket until almost full.

2. Pour enough water into the bucket to soak the paper strips.

3. Tamp the paper down with the paint mixer to compress it slightly so it is beneath the water level by at least two inches.

4. Let the paper soak for 24 to 48 hours. You could also boil the paper in a large stock-pot for 30 minutes if you’re in a hurry.

5. Attach the paint or stucco mixer to the drill and move it around in the paper to shred the paper to a pulp. Experiment with drill speeds to determine which speed does the best job based on the power of your drill.

You’ll want to do this out in the yard and wear old clothes. The pulp will splatter from the bucket and can splatter both you and the surrounding area.

6. Continue to pulp the paper pulling up the mixer from the bottom and sides. If the mix is too dry and resists pulping, add water. If the mix is too wet, drain off some water from the top or add more paper. (You can add small proportions of dried paper if necessary, but tear it into small pieces).

7. The final pulp should have the consistency of cottage cheese or lumpy oatmeal.

8. Once pulped, you can add a quart of bleach if you want to diminish the grey color. Pour in the bleach and continue to pulp and distribute the bleach with the mixer until blended. As the paper pulp soaks, the color will bleach to a light greyish-white.

Don’t get your hopes high. You will never get pure white. If you choose to bleach the pulp, know that any splatter that hits your clothing will bleach it in spots, so dress accordingly. You’ll also be unable to dye the papercrete. The bleach will cancel it out or turn it into a very muted color.

9. Strain the pulp through a colander or, for larger batches, improvise a strainer with a screen supported by chicken wire on a wood frame.

10. Reserve the pulp for the final formula.

Basic Papercrete Formula:

- 5 parts paper pulp

- 2 parts Portland cement

You’ll need another 5-gallon bucket for this step. If making a larger quantity, you could use a wheelbarrow or concrete trough. You’ll use a trowel to mix the paper pulp and cement for smaller quantities. You could also use a shovel if mixing in a larger container.

Basic Papercrete Directions:

1. Add the proper proportion of paper pulp to the mixing container (we’re using 5 parts paper pulp in a 5-gallon bucket).

2. Add the proper proportion of cement next. (For this example, we’re using 2 parts cement.)

3. Begin blending the mixture using the trowel. If it gets too dry, add some more paper pulp. If it’s too wet, add more cement.

4. When done, it should have the consistency of chunky pudding.

5. It should not settle when placed on a board, but hold its shape. If so, you’re now ready to trowel it into a form. If you are applying it to the side of a mold for a pot or other object, you’ll want to have a thicker consistency so the wet papercrete will not slide down the mold.

It’s easier in a form for a brick because the sides of the form simply contain the wet papercrete.

6. After 20 minutes, the papercrete will start to settle.

That’s the time to add a little more if you want a uniform shape for a brick.

Use a trowel to smooth the top of the papercrete if you’re making a brick. If you’re using a mold for a pot or object, apply and smooth with your hands. You’ll want to check the sides to make sure none of the papercrete has slid down.

7. Cover the mold or form with plastic wrap for 24 hours to let the papercrete slowly cure, then remove the plastic wrap and remove the form to allow the papercrete to stand freely for further drying.

8. Let dry for another 2 days.

9. If drying outdoors, cover it with a loose-fitting tarp to prevent morning dew or rain from coming in contact. If making papercrete in winter, you’ll need to let it dry in a relatively warm area like a garage or a place where you have improvised some form of heat.

10. Something as simple as covering it with a black tarp or a black plastic garbage bag could capture enough heat from the sun to do the job during a cold day.

Papercrete Formula Variations

Papercrete will shrink when drying and will settle when first put into a form. The amount of shrinkage is proportional to the amount of paper pulp in the final mix. Basic papercrete will shrink by 15 to 25% while drying.

If you are making bricks, you should add some papercrete to the form 20 minutes after your first pour if it’s settling, or design a form that will allow you to overfill it to compensate. The more cement you add to a papercrete mix, the less shrinkage and settling, going as low as 3 to 5%.

If you want to make papercrete mortar or plaster, mix paper pulp with cement in a 50/50 proportion.

If you want to increase load-bearing properties, use this formula:

- 5 parts paper pulp

- 3 parts clay

- 2 parts cement

- 1 part sand

If you want to increase insulation value where load-bearing is not critical, add more paper pulp. You should always have some cement in the mix (at least 10%), but you can and should experiment with various pulp proportions if you are embarking on some serious papercrete construction.

If you want to significantly increase load-bearing, do the 5-to-2 proportion of paper pulp and cement we demonstrated.

Avoid the temptation to simply use paper pulp only. That’s paper mâché, not papercrete. Paper pulp alone, when dried, is very weak in terms of load-bearing and also flammable.

There are other variations on papercrete formulas on the Internet that various papercrete masons swear by. We’ve covered some of the basics, but if you’re serious about papercrete, you’ll most likely develop your own favorite formula.

Totally Off the Grid

While it’s a bit messy, making papercrete is fairly easy. Especially with things like Perlite, power tools, ample electricity, lots of paper, and easy access to a hardware store for cement. But in a serious or sudden off-grid environment, you’re going to have to improvise. Let’s consider the tools and ingredients and think about options.

Water – No problem here as long as it’s raining or snowing from time to time. Besides, if there’s no water anywhere, you’ve got bigger problems than trying to figure out how to make papercrete.

Perlite or Vermiculite – Dirt and sand are easy substitutes. The benefit of fillers like Perlite or Vermiculite is that they’re lightweight and add to the insulating value of papercrete. While dirt and sand are heavier, they perform the same purpose to add structure to the papercrete and add some load-bearing properties as well.

Cement – Two options here. The easy one is to use clay. Dig deep enough in the ground and the chances are good you’ll hit a layer of clay. Adobe bricks are primarily made out of clay and when mixed with paper pulp, they can form a very good variation on papercrete. It’s more susceptible to water, but in a dry environment, it works fine.

The second option is to make Old Roman Concrete. It’s an ancient recipe dating back more than 2,000 years. We’ll cover that in a separate section because it’s a bit complicated.

Paper – Believe it or not, paper may quickly become a scarce commodity in an off-grid economy. The solution is to find a natural source of cellulose that has a fibrous composition. It’s the fibers in paper that give papercrete structural integrity, and you need that if you’re making it with a paper substitute.

Here are some good examples to look for:

- Burdock Stems and Burrs – These are highly fibrous. Their most common identifying characteristic is the cockle burrs that attach to our clothing during a casual walk in the woods and fields. In fact, the Romans used to make rope out of the stalks of Burdock after rubbing the stalks into fibers.

Dead Burdock is best after it has turned brown and is dry. If green, set the stems out to dry in the sun. Cut the stems and crush the burrs and toss them in the bucket along with some other good cellulose substitutes.

- Dried Grasses, Straw, or Hay – Grass is also highly fibrous, especially the seed stalks. Like Burdock, dead grasses that have dried seem to work best as a paper substitute for papercrete. Chop or use scissors to cut them into lengths about 2 to 4 inches long and soak and pulp them the same way as paper. If the grass is green, dry it in the sun and then cut.

Other plants with fibrous stalks or stems like cattail or horehound also work well.

Plants That DON'T Work As Paper Substitutes

- Leaves – It would seem that leaves could be a good substitute for paper, and while they have cellulose, they’re missing something: “Fibrous” Cellulose. Leaves have thin veins to carry water and nutrients, but the leaves themselves are fragile–especially when brown and dry–and don’t have strong fibers for support. Banana leaves are an exception, but most of us don’t have bananas growing in our backyard.

- Bark – Like leaves, bark also doesn't have enough fibrous cellulose. It has multiple bark layers on the trunk of a tree to do the same things, but bark is largely unaffected by water and won’t pulp well.

Natural Dyes

Many of us have found dyes in nature without even trying.

If you’ve ever spent time as a kid eating mulberries off a tree, you know how effective they can be when it comes to stains. Red Sumac berries are another example and can be added whole to off-grid papercrete while mixing. Other berries to consider include blackberries, black raspberries, and blueberries.

It’s best to mash them to release their juice and their color and then add the juice to the pulping bucket as you mix.

Making Papercrete the Off-Grid Way

While there are many natural sources of fibrous cellulose, there are only two options for a binder to replace store-bought Portland Cement: Ancient Roman cement and clay.

Of the two, clay is the easiest, but you’re going to have to dig to find it. It also doesn’t provide as much load-bearing strength as cement. And like paper pulp, it is vulnerable to moisture.

Adobe bricks are largely made from clay but most of the buildings constructed from Adobe bricks were built in desert areas where moisture was less of a concern. If you live in the desert, go for it. If you don’t, it’s worth taking a look at an old Roman formula for cement.

Roman Concrete and Cement

The Romans built their aqueducts, baths, some of their roads and harbors, and even the Pantheon using concrete. The Pantheon is a domed structure built with concrete that has stood without wear for more than 2,000 years.

The Romans didn’t mess around, and because their concrete pours had such a high concentration of their cement, they didn’t need rebar to reinforce walls and ceilings. The problem with rebar in concrete is that it eventually rusts and causes the concrete to crumble. The Romans didn’t have that problem.

In case you’re wondering, the difference between concrete and cement is that concrete is a combination of cement, sand, and gravel. Cement is a different story.

Roman Cement Formula “Opus Caementicium”

The original formula for Roman cement was lost for centuries and rediscovered in the 1700s by a French Engineer. Romans would take chunks of limestone and place them in a kiln. The high heat burned off carbon and oxygen in the limestone and left behind something called quicklime.

The resulting quicklime was then crushed to a powder and added to water to make a paste known as hydrated lime. This is the basic Roman cement that you could use with your natural, fibrous cellulose pulp to make papercrete. Assuming you have a kiln and access to limestone.

To make your papercrete, add 3 parts of natural cellulose pulp to 2 parts clay or 1 part of Roman cement (hydrated lime) and mix. The result will be similar to traditional papercrete and the color of the finished product will be a light shade of your pulp material and binder.

Cutting and Mixing Natural Cellulose

Without electricity, you won’t have the luxury of a power drill with a paint mixer, but if you have the mixer attachment, you can attach a handle to the top and press, twist, and turn by hand. A stucco mixer works best because it has the sharpest blades, but watch out for the sides of any plastic bucket.

It also helps to cut any grasses or stems as small as possible and smash them between two flat stones before soaking them in water. You can also dive in and use your hands to tear, mix, and crush. A branch about 2 inches thick with nails driven into the end can also be dropped, lifted, and dropped again and again into the mix to work the pulp.

It’s worth experimenting a bit with this off-grid approach if you think you’ll ever have a need for this type of masonry.

Scaling Up Papercrete

It’s time to get back on the grid and get serious. What we’ve explored so far is on a very small scale using 5-gallon buckets and single forms for a couple of bricks. If you’re planning larger projects with papercrete, you should do a few things:

- Experiment with formulations to suit your end use. If you’re looking for load-bearing, you’ll want to do some tests to see how a brick stands up to weight. You might also want to simply experiment with formulas and proportions to see what you think of the results.

- While you’re at it, experiment with mortar formulas. Most large-scale construction with any kind of masonry requires mortar. The standard formula is a 50/50 mix of paper pulp to cement, but see what happens if you vary that to 60/40, etc.

- Think mass-production. Don’t build a form for a single brick. Build long, multiple-brick forms from 8 to 16-foot 2 x 4’s in quantity so you can pour and form multiple bricks per batch.

- Scale up your mixing equipment. A 5-gallon bucket and a hand drill will make for long days and tired arms. But be forewarned. A traditional, standing cement mixer won’t cut it. That’s because it literally won’t effectively cut the paper into the shreds you need to make a pulp. Check the Internet with a search for “papercrete.” Many papercrete masons have constructed some simple and effective ways to mix large batches of paper pulp.

- Get the word out to friends, family, and neighbors that you want their paper. You could also check in with grocery stores and retailers who throw out large bundles of cardboard on a regular basis. You could even ask your local recycling center if you could have some paper. They might surprise you and just point you to an over-flowing paper dumpster.

- If you have the time, do some moisture tests on different papercrete formulations. It’s unreasonable to wait years for results, but after a couple of weeks or months you might start to understand the dynamics of papercrete and moisture a little better.

Beyond Papercrete

As a self-reliance skill, the ability to make papercrete can be very valuable. While you’re thinking about things like papercrete, it may be worth some time to look into Adobe construction, Fidobe (which is made with clay and shredded cloth), and other alternative building materials.

All of these can save you a lot of money, they have an attractive, rustic look, they can be painted and shaped to suit your eye, and they can give you another way to achieve self-reliance. It’s also fun and, at least on a small scale, easy to do.

Like this post? Don't forget to Pin It on Pinterest!

You May Also Like:

Could sawdust be subsituted as paper?

I checked with the author, and he says that might work, but it’d need to be the finest sawdust possible. If you do that, soak it and mix it to a pulp with water until it has the consistency of porridge before adding the cement.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pykrete

Amazing and detailed turorial thanku very much…cheers ?

thank you for this info.

I would look at the rototiller for a big mixer. and a log splitter to compress

the pulp into a long “log” to then cut into “bricks”

and use pallets to dry bricks.

Good luck All. !

Sounds cool to me ?

Someone locally was making sawdust-crete building blocks commercially out of sawmill leftovers and Portland. I would say the sawdust was fairly coarse. Think chainsaw leavings.

Shaped like standard 12 inch concrete blocks.

Recommended use was stacking dry, then filling cavity with pieces of rebar and thin concrete mix for final stability. Parging (stucco) was recommended on weather or animal exposure surfaces.

The farm building I’m aware of lasted 30+ years.

I am making a modified with added polymer blend a d have had great results for large outdoor sculptures

Wow ! I cannot believe this post. I was thinking some time ago if there was some way that I could use my old newspapers and books to make small storage cubes for my crafting stuff. I thought papier- mache, using glue .Now I have the perfect answer. Thank you!

How would horse manure work for fiber and mixed with cement?

I’d love to hear if anyone has used manure with good results, we get 300 lbs per day from our horses.

Don’t think that I would build a house out of it. lol

I’m familiar with this building technique. I suggest you do a little more research and learn some more effective techniques. Especially if you are sharing information with others. Papercrete units can be much larger than bricks. you can create molds the size of 12x24x6″ for instance, they are light weight, easy to build with. You can create a multiple unit form. Watch videos. And don’t consider coloring them with berry juice. Anthocyanin, the colorant, from purple fruits is extremely impermanent and PH sensitive. High PH will turn purple to blue, green, grey, depending. Use pigments instead, which are colored particles. Colored earths will work. Dyes do not hold up under sun exposure. The information is out there if you look for it. Eve’s Garden Motel is a great papercrete project located in Marathon, TX. It is doable for sure.

On the bag of cement, it suggest adding lime to the cement for curing along with sand or gravel. In making paper Crete the recipes don’t call for lime. Why is it that you don’t need lime in the process of making paper Crete?

Avoid vermiculite, it’s known to contain asbestos and is now considered a hazard.