Estimated reading time: 20 minutes

Plants and Winter Don’t Mix, but There’s Still Plenty to Forage if You Know Where and How to Look.

Plants and Winter Don’t Mix, but There’s Still Plenty to Forage if You Know Where and How to Look.

Foraging for wild edibles is hard enough in the spring, summer, and fall, but winter is the real challenge. Fortunately, some plants will surprise you with the treasures they leave behind.

Want to save this post for later? Click Here to Pin It On Pinterest!

There are numerous possibilities for winter foraging, but some just aren’t worth the trouble or the risk. Mushrooms are a good example, and while many mushrooms appear in winter, the vast majority of mushrooms in North America are toxic, but we’ll cover that later.

Think Outside The Summer Box

Foraging in winter isn’t about eating leaves and fresh, wild fruit. You have to understand some of the other parts of plants that can give you the nutrition and calories you need that can survive the cold weather. In this article, we'll cover six options.

Quick Navigation:

The Big Question: Nutrition?

On a basic level, nutrition is all about vitamins and minerals. They’re the trace elements we need to function, support our immune system, and fundamentally operate that machine known as the human body.

But every machine needs energy and for us, that comes from calories. And that’s where the classic wild foraging challenge emerges. Many plants are very low in calories although they do deliver good doses of vitamins and minerals.

Calories aren’t an issue if you’re casually wild foraging, but in a survival situation, calories are king.

Calories 101

Calories are derived from two basic sources. Calories from carbohydrates and calories from fat.

Calories from carbohydrates come from the natural sugars in food. It’s called fructose and it gives you a burst of energy that fades after a while.

Calories from fat are derived from oils whether it’s animal fat or vegetable oils. The benefit of calories from fat is that there tend to be more calories in fats than in sugars. More importantly, calories from fat have been shown to be highly effective at generating internal body heat for longer periods of time. It’s why Arctic explorers thrived on pemmican which has a very high-fat content.

This comes down to the big question. Where do you find calories from fat in plants during the winter when you can hardly find them in summer? The quick answer is “nuts” and we’ll go into detail on where to find them and how to prepare them.

There’s Always a Catch

Preparing winter foraged plants is time-consuming and labor-intensive. That’s the catch. You can eat berries right off the vine in July and eat leaves right off the plant most of the year, but it all changes in winter.

Roots have to be dug out of frozen ground or freezing water, nuts have to be found, cracked open, and sometimes soaked in water for hours–it’s a lot of work.

The Challenge of Accurate Plant Identification

It’s hard enough sometimes to identify wild plants at their peak in summer, but without leaves on the plant and with more than a few buried under snow and ice, it can be difficult to identify a plant let alone find one.

Fortunately, some plants like cattails retain enough of their structure to make them easy to identify. The same goes for trees if you have a fundamental knowledge of their shape and bark. The best-case scenario is after any thaw which reveals part of the ground and maybe some dead leaves to give you some clues.

We’re also going to try and focus on those wild food resources that are easy to spot in winter.

Wilderness Awareness

This isn’t about sitting on a bed of pine needles and meditating. It’s about stepping back and looking at the big picture of what’s around you to consider the winter foraging possibilities.

- Are there any nut-bearing trees in your field of view that you can recognize by shape or dead leaves still on the tree or on the ground?

- Do any trees show lichens that can be harvested?

- Are there any plants showing unique characteristics even in winter like cattail stalks sticking up from the snow and leading you to their still edible roots?

- Are there any spots of green in an otherwise monochromatic landscape indicating a hardy, winter survivor?

- Are any frozen fruits visible on a tree or bush-like crabapples?

Taking the time to stop and survey the possibilities is a lot more productive than hoping you happen across a wild edible underfoot as you walk or randomly dig through the snow.

Wilderness Survival or Homestead Supplement?

It’s easy to assume that wild foraging is all about finding food in a wilderness survival situation, but there are many of us that make wild foraging a regular activity to supplement our daily meals. That’s an important consideration because your ability to prepare a wild forage at home is a lot easier than a wilderness survival situation with limited resources.

Boiling maple sap into syrup is a wild forage but who has the time or the equipment when you’re lost in the wilderness and have so much else to do? As a result, we’ll cover the worst-case, wilderness survival prep steps and then cover how you could also take it up a notch at home.

The Top 6 Winter Plants for a Survival Forage

Nuts top the list because of their high-calorie count and the number of calories from fat. You’ll have competition from rodents and especially squirrels, but if you spot an isolated tree that’s some distance from other trees, your odds of finding nuts on the ground will improve. Squirrels don’t travel across open spaces and prefer areas where trees are concentrated to easily escape predators.

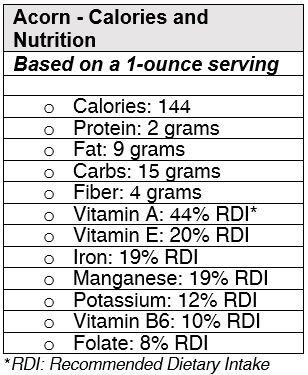

1. Acorns

Acorns are an excellent source of calories from fat and can easily be found on the ground through winter.

Location Tips

Oak trees are common in deciduous forests across North America. Basic varieties include White Oak and Red Oak. White Oaks are preferred because their acorns have less tannic acid or “tannins” than Red Oaks.

Identification

White oaks tend to hold their leaves through winter while Red Oaks tend to shed their leaves in Autumn.

You can also look for oak leaves scattered on the ground to help identify the tree as an oak.

Red oak bark tends to be thick with prominent fissures.

White oak bark tends to be thinner with a chip-like appearance.

Preparation

To prepare acorns you need to remove the cap and the outer shell needs to be cut and peeled away. The acorn kernel should be white to a light yellow. Coarsely chop them and soak them in water for an hour and then add fresh water and soak them again for another hour. Taste as you go until they’re not bitter.

In a survival situation, you can eat them raw after soaking, or you can soak and roast them on a log next to a fire. At home you can process them in a food processor, soak them again and strain through cheesecloth and dry them in the oven at 250°F. When dry, process into flour for baking.

Tips and Cautions

The standard caution is to never eat a raw acorn. All acorns should at least be soaked or boiled in water to remove tannins.

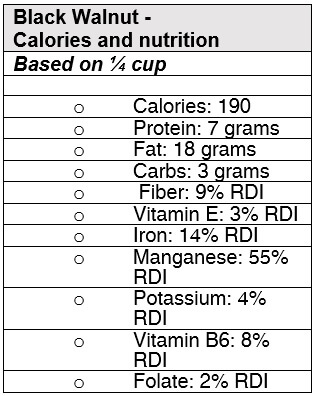

2. Black Walnuts

Black walnuts are another excellent source of calories from fat and the health benefits of walnuts have been widely touted.

Location Tips

Black Walnut trees are also common across deciduous forests of North America.

Identification

Their leaves are pointed rounds joined to a stalk with numerous leaves running the length.

The bark is rough and deeply fissured.

Black walnuts are actually bright green when they first fall from the tree and gradually turn black.

Preparation

1. Removing the outer shell

Put the walnuts on a flat rock and gently roll them back and forth with your boots. Other techniques for removing the outer shell include rolling them between two boards or putting them in a burlap sack and forcefully hitting the bag on a hard surface.

2. Rinsing the nuts

Fill a bucket with cold water and dump the shelled walnuts into the water. If any of them float, discard them. Floating means that the nut has either been compromised by insects or the inner nut-meat has dried or spoiled. Good black walnuts sink.

Soak them overnight and in the morning, drain the water and refill. Continue to repeat this cycle of refreshing the water until the water remains clear.

3. It’s a tough nut to crack

Use a hammer or a rock. Wrap a few nuts with a washcloth or a piece of burlap and gently smash them with the hammer until they open. You can then pick out the nut-meat and discard the outer shells.

The reason you want to wrap them in some kind of fabric when doing this hammer technique is to avoid the shrapnel and shattering that could strike your eyes. You could also use a vise at home.

4. Roasting black walnuts

Once you’ve cleaned out the nut meat, you can give your walnuts a light roast. Roast them for about 15 minutes at 325°F in an oven or on a log next to the fire. Taste them after 15 minutes to see if they need more time.

Tips and Cautions:

Don’t roast them in the shell. They will explode and shatter.

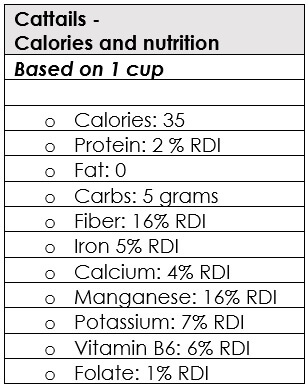

3. Cattail Roots

Winter is actually the best time to harvest cattail roots because the plants have had the full season to mature.

Location tips

Cattails grow near and in water so any visible water source is worth a look.

Identification

Cattail stalks are still visible in winter and their fluff makes for great tinder for a fire. The stalks are also a great signpost for the roots and tender shoot beneath.

Preparation

This is a chilling harvest especially if you have to pull them from frigid water. You’re looking for two things: the roots and the green stalk just above the roots.

Trim the roots and peel them. You’ll end up with something resembling a raw French fry. You can eat them raw after washing in clean water or roast them on a stick over a fire. You could also boil them or deep fry them.

The tender bottom can be cut up like a leek and after a thorough rinsing in clean water, you can eat them raw or toss them in a salad or make a soup out of them with some chicken broth.

Cautions

Cattails tend to grow in still, stagnant water and even in winter, there’s the potential for bacteria in the water to contaminate any part of a cattail. Wash them in clean water and cook if possible.

4. Lichens

Lichens have been on Earth for billions of years and are one of the oldest forms of life on the planet. Equally surprising is the fact that some lichens can be hundreds if not thousands of years old.

And there’s good news in lichen land. Out of the 20,000 or more species that grow across North America, only a very few are toxic. Any lichen that has a yellowish or orange color is toxic but even the blue-green ones need to be at least soaked in water before consuming.

Location Tips

Lichens grow on all species of trees but tend to favor oaks and maples. Chances are good that if you see a lichen growing on a tree there will be many more nearby.

Identification

There are three basic types of lichens:

- Foliose (leaf-like)

- Fruticose (shrub-like)

- Crustose (growing closely attached to a surface)

All of the blue-green variety of lichens are edible.

Preparation

A raw lichen right off the tree or a rock is going to have the consistency of a rubber inner-tube and taste highly acidic if not down-right astringent. The fact of the matter is you have to soak them in water for hours with frequent water changes. This will get rid of the natural acids that permeate the lichen.

A Japanese technique is to gently boil them with frequent water changes. This will result in a lichen that is quite gelatinous. In case you’re wondering, “gelatinous” means slimy similar to the slime you see when you boil okra or cactus. It’s okay to eat it, but be prepared.

In a pure survival situation, you would soak the lichens in water with frequent water changes and eat them like potato chips. They’re going to be tough, blue or green potato chips, but they’ll help to keep you alive.

In a more civilized environment, you can slice them and toss them in pasta with olive oil, or add them to a soup or broth to thicken the soup. Even in a simple cup of chicken broth, lichens will add viscosity and body, making it sip more like gravy than a watery broth.

In Africa, lichens were used for jelly making with locally harvested fruits. It has the same qualities as gelatin and was also used by American pioneers before commercially made gelatin became available.

Lichens – Calories and nutrition

Nutrition information on lichens varies widely due to the range of varieties and environments. Generally, they are touted as a good source of calcium, Vitamin-K, relatively high calories from carbohydrates, and relatively high in proteins including amino acids.

Tips and Cautions

Avoid yellow, orange, or red lichens. They are toxic. Stick with the blue-green varieties. All lichens also have varying amounts of acidic compounds that must be leached out with soaking or boiling in water.

5. Frozen Crabapples

Location Tips

Wild fruit trees tend to be shorter than most other trees in a deciduous forest. Most lose their fruit in Autumn but some trees, particularly crabapples, seem to hold onto their fruits into the winter.

Identification

If you see a smaller tree that still seems to have fruit on its branches, check it out. If it’s a wild crabapple and the fruits are still frozen on the tree you’re in luck. You’ve just found one of the very few natural sources of Vitamin-C in winter.

Preparation

Your luck continues because you can actually eat them right off the tree. They taste like a frozen dessert. You could also cook them in water to make a syrupy porridge. If you find a tree with frozen fruits, collect as much as possible. Natural vitamin C is hard to come by in the dead of winter.

Cautions

Just be sure it’s a wild crabapple and taste as you go. If it doesn’t taste right, spit it out and move on.

6. Mushrooms

Here’s the telegram: Of the 10,000 species of wild mushrooms in North America, 96% are toxic and 4% are deadly. Wild foraging any mushroom is a very dangerous game and a survival situation is not the best time to take any risks.

It’s true that many mushroom species grow in winter, particularly enoki mushrooms which prefer rotting trees and stumps. Unfortunately, a look-alike known as the Galerina grows in the same environment and it’s quite toxic.

What makes mushrooms so appealing for winter foraging is how they continue to show up more than any other plant in winter.

The most common appearance is from tree brackets or shelf mushrooms many of which are toxic.

If you think you might want to consider foraging mushrooms at any time of year, do your homework. Field guides are available and the Internet is awash with information about wild mushroom foraging. All of them offer the same caution: be careful out there when foraging wild mushrooms.

Yes, There’s More

We tried to focus on the low hanging fruit, so to speak. There are other winter foraging options like tree bark and pine nuts but the effort and the nutritional reward are questionable in a survival environment as challenging as winter. There are also temperature variations across North America where more temperate zones offer more options than parts farther north.

If you’re aware of something we missed or something unique to your area that you’ve either found or foraged in winter, please share in the comments section below.

Like this post? Don't Forget to Pin It On Pinterest!

With regard to cattail roots, it’s more than stagnant water and bacteria you need to beware of. If the wetland is near old mines or other contaminating sources, don’t eat the roots. They collect the contaminants and help to purify, I use the term loosely, the water. I live near abandoned coal mines which dump sulfur and iron oxide into the water. The cattails pick these up. The water at one edge of the wetland is full of contaminants and no creatures live in it; the other edge had tadpoles swimming around in the cleaner water. So be very aware of where the water comes from.

Another thing about cattail harvesting, especially in the winter, is to be absolutely positive the roots you are digging are cattail and not wild iris which frequently grow in the same wetland and in among the cattail. The iris roots are poisonous.

Your print option is crosslinked with Pinterest and populates the printed item with Pinterest pages