Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

In his introduction to Stalking the Wild Asparagus by naturalist Euell Gibbons, John McPhee recalls speaking with Gibbons about his childhood.

“Euell had begun learning about wild and edible vegetation when he was a small boy in the Red River Valley. Later, in the Dust Bowl era, his family moved to central New Mexico. They lived in a semi-dugout and almost starved there.”

After Euell Gibbons’ father left to search for work, the family’s food supply diminished until all that was left were a “few pinto beans and a single egg, which no one would eat.” Drawing from his earlier foraging experiences, the teenaged Euell Gibbons — one of four siblings — headed out to find food.

Want to save this post for later? Click Here to Pin It On Pinterest!

He returned with a knapsack full of piñon nuts, puffball mushrooms, and prickly pear fruit. For nearly a month, the family was able to survive solely on what Gibbons foraged.

“Wild food has meant different things to me at different times,” Gibbons told McPhee. “Right then, it was a means of salvation, a way to keep from dying.”

Although this experience may seem extreme, many Americans who lived through the 1930s have similar foraging stories to share.

In Wild Seasons, author Kay Young shares the story of a retired meter reader who recalled seeing bathtubs full of the lamb’s quarters that were being washed for cooking and canning in Kansas City homes in the 1930s. The nutritious green was one of the edible plants growing in and around city lots.

Between factory layoffs in the cities and crop failures in the farmlands, the heydays of American life in the 1920s became a distant memory. Historians estimate that about one-fourth of the U.S. population was hungry at various levels from 1930 through 1941. By one count in 1932, there were as many as 82 breadlines in New York City.

More than 50,000 New Yorkers were homeless by the end of that year.

By 1939, around 60 percent of rural households — and 82 percent of farm families — met the federal classifications for “impoverished.”

Yet, despite the hardships that befell them, most Americans learned to “make do” with much less. And we can learn from their thriftiness and ingenuity today as we face difficult times. In this article, we list and describe 15 of the wild edibles that people foraged during the Great Depression.

1. Lamb’s Quarters

Often called “wild spinach,” lamb’s quarters is a common garden weed that is nutritious, tasty, and easy to harvest. All parts of the plant are edible, but the flavor is best when the leaves are young and tender in the spring and early summer. You can harvest its edible seeds in late fall.

Here’s information on how to cook lamb’s quarters.

2. Purslane

Depression-era foragers also found purslane in abandoned lots and backyards. Known for its high mineral content, this wild plant has distinctive fleshy stems and jade-like leaves. You can eat it raw or sauté it as you would other greens.

Here are 20 recipes for purslane.

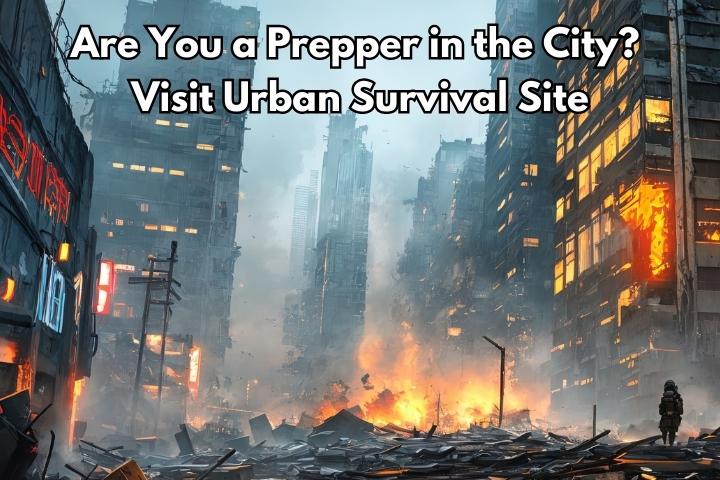

3. Tumbleweeds

Contrary to the image you might have of tumbleweeds (Russian thistle) from old Western films, parts of the plant are tender and edible when they are young. Historians believe that cattle survived during the Dust Bowl of the 1930s thanks to the availability of the invasive thistle.

And hungry people in the Dust Bowl-ravaged states of the Midwest and Southwest found ways to cook and eat tumbleweeds themselves. Primarily, they chopped them up and added them to soups and salads to gain the nutrition they provided.

Here are ideas for foraging and eating tumbleweeds.

4. Tubers

We typically think of potatoes when we think of “tubers,” but many plants have edible root or stem structures. Wild tubers became an important way to feed a hungry family during the Great Depression. Here are some plants that have edible roots and tubers:

- Daylilies

- Cattails

- Dandelions

- Burdock

- Chicory

- Kudzu

This article offers tips for finding, cleaning, and preparing tubers for eating.

5. Pawpaw

Some people say it tastes like a cross between a banana, a mango, and a pineapple. Whatever you make of its tropical flavor, you might want to know more about the pawpaw, a largely unknown North American fruit that grows wild in 26 states. You eat the fruit’s nutritious pulp raw or add it to recipes.

6. Timpsula (or tinspila)

Nicknamed the prairie turnip, this root vegetable was a mainstay for many Depression-era families. The prairie turnip’s root forms a long, thin tuber about four inches below the ground.

It has a thin skin that can be easily removed to reveal a white flesh that is high in protein, starch, and vitamin C. Thrifty cooks boil and mash it as you would a potato, or they add it to soups and stews.

Here is more on how to forage and cook the prairie turnip.

7. Dandelions

During the Great Depression, “waste not, want not” was the mantra of many folks. The easy-to-find, easy-to-harvest, and entirely edible dandelion fit the bill well.

Dandelion greens are at their tastiest in the early spring. You can sauté them in olive oil and add them to many recipes. You can eat the flowers in a salad or dry and roast the roots as a coffee substitute. Here is how to forage and cook the humble dandelion.

You’ll find links to some dandelion recipes at the end of this helpful article.

8. Mushrooms

Foraging wild mushrooms is a bit of an art and a science. And, just as with all the plants mentioned in this article, it is essential to know with certainty that the mushrooms you forage are safe to eat. Folks during the Great Depression used mushrooms in many ways to add to their meals, often frying them or mixing them with potatoes or other carbohydrates.

You can forage for wild mushrooms in damp forests and woodlands, and the most common edible varieties are morels, chanterelles, and giant puffballs. Use a detailed field guide or app to help you determine which ones are edible, and if in doubt, do not eat them.

9. Acorns

We could learn a thing or two from the squirrels that busily gather and store acorns in the fall for their winter food stores. Our Depression-era forebears took note and found many ways to use this plentiful gift from the oak tree.

Here are tips for gathering and preparing acorns for eating. One of the essential steps is removing the bitter-tasting tannins. Afterward, you can grind acorns to make flour or coffee.

10. Huckleberries, blackberries, and raspberries

Wild berries were a vital source of nutrients for many Depression-era families. Depending on where you live, you may have access to wild berries in parks, forests, and fields. Be sure to check the rules in your area for foraging and make sure the berry plants have not been sprayed with pesticides.

11. Fiddlehead Ferns

Depression-era home cooks were adept at making soups and stews because they helped them stretch what little food they had. Young fern heads that appear in the spring in damp, wooded areas are packed with nutrients and provide taste and sustenance to soups and stews. Here is how to find and prepare fiddlehead ferns.

This video explains the foraging process and how to use this wild, versatile vegetable.

12. Milkweed Pods

The milkweed plant grew plentifully across the U.S. in the 1930s, and many foragers collected the pods in the fall. Because of their shape, size, and taste, some people refer to milkweed pods as “wild okra.” Here is information on harvesting and cooking wild milkweed pods.

13. Nettle Leaves

Think of how hungry the first (or second or umpteenth) person was to harvest stinging nettle leaves. The leaves may be covered in spikes, but those in the know are willing to contend with the sharpness to access the nutritious food contained inside.

The best time of year to harvest nettle leaves is in the spring or early summer before the plant flowers. Use thick gloves and a pair of gardening scissors as protection.

Here is how to cook and eat nettle leaves.

14. Sorrel

Wood sorrel and sheep sorrel are packed with vitamins and other essential nutrients, and you may find them growing right in your own backyard. Depression-era families often used sorrel as a substitute for lettuce.

This video shows you how to find wild sorrel and use it as a soup ingredient. When eaten raw, sorrel has a fresh, lemony taste. For more information on foraging and eating wild sorrel, check out this article.

15. Shepherd’s Purse

You might find shepherd’s purse (also called lady’s purse) growing along your driveway and in untended parts of your yard. You can eat the leaves and flowers raw or cooked. The seed pods add crunch and texture to salads and can be used as a pepper substitute.

Here’s more on identifying and eating shepherd’s purse, including its medicinal uses.

Foraging is a skill that can come in handy if your food supply is jeopardized. Although reading about wild plants you can eat is helpful, you can learn the most by doing. You may want to consider a class or group to help guide you on foraging methods.

After some trial and error, you’ll find it a rewarding practice that saves you some money and offers you peace of mind.

Like this post? Don't Forget to Pin It On Pinterest!

You May Also Like: